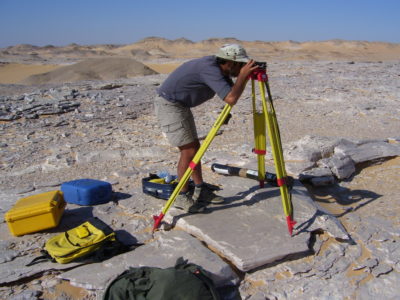

Italian Archaeological Mission to the Farafra Oasis (Western Desert, Egypt)

The Farafra Oasis prehistoric research project was begun in 1986 by Barbara E. Barich, then at the Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Antichità of the University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’, and is currently co-directed by Barbara E. Barich, and Giulio Lucarini of the University of Cambridge, UK. The mission is currently organized by ISMEO with funding from the MFA and Cambridge University.

Co-directors: Barbara E. Barich, Giulio Lucarini

Nation: Egypt

Period: 1986 – in course

Farafra, together with Bahariya, Dakhla and Kharga, is one of the oases in Egypt’s Western Desert. The mission’s central goal is to understand the economic development that occurred in this extensive territory, with the fundamental transformation from a hunting-gathering model to early forms of horticulture and animal domestication. The data obtained in the field are studied with reference to the Nilotic societies that developed the first forms of agriculture during the Badari and Naqada cultural phases (5th– 4thmillennium BC).

After 20 missions in the field and studies conducted by a multidisciplinary team, the Farafra oasis, once an unknown territory, today has a place in the cultural history of pre- and proto-historic Egypt thanks to the archaeological, geomorphological, palaeo-climatic and bioarchaeological reconstruction of the region. In the 7thand 6thmillennium BC in the Western Desert a veritable Oasis Culture developed, of which Farafra today preserves the most complete and detailed remains. In the north of the depression, the Hidden Valley and Sheikh el Obeiyid villages have shown the emergence of a Neolithic culture characterized by semi-sedentary village settlement, increased social complexity and high-standard stone hand-axe technology. The economy featured the first forms of goat-breeding, combined with intensive collection of the wild grasses that grew locally, among which the use of sorghum is of particular interest. The presence of goats, not an autochthonous North African resource but imported towards the end of the 7thmillennium BC, demonstrated significant relationships with Near Eastern communities, and this introduction of the first animal-raising led to an economic transformation. An important glimpse of the symbolic world of Farafra’s Neolithic inhabitants is given by the engravings and paintings on the walls of a cave in Wadi el Obeiyid, just two kilometres north of the Hidden Valley village, itself a significant ritual and cult location for groups transiting in the area. In summary, the Farafra region was home to largely autonomous agro-pastoral activities that were transferred to the Nile Valley during the most arid phases of the Holocene (> 5200 BC), thus influencing the development of pre-Dynastic Neolithic cultures.