11 May Tha Kae 1988-1993

Archaeological investigations in Tha Kae 1988-1993

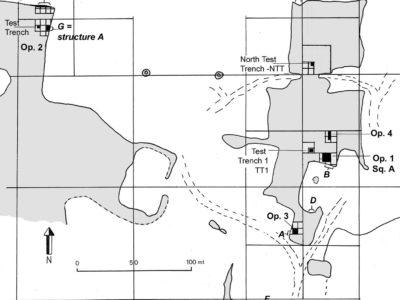

Our fieldwork began in 1988 with a rescue excavation programme on the Tha Kae site (Lopburi District, Province of Lopburi, 14°50’40” N- 100°37’10’’ E) [Fig. 1], which was on the verge of being completely destroyed by quarrying activities and illegal digging – that forced the abandonment of the excavation in 1993 [Figs. 2, 3]. Located on a river terrace cut by a palaeochannel [Fig. 4], in aerial photographs taken in 1945 and 1953 the site appeared clearly surrounded by a double moat and embankment, with an area of about 73-76 ha, of which today only traces remain [Fig. 5]. Four excavation campaigns (1988-1993) at Tha Kae enabled the history of the archaeological deposit to be understood, with occupation phases dating to the early 2ndmillennium BC and the 17thcentury AD [Fig. 6].

The project’s main objectives were: to understand how the archaeological deposit was formed, identify the structural and cultural phases, study the craft activities conducted on the site, and the nature of, changes in and scope of cultural and commercial interactions at regional and inter-regional levels. After a first campaign (1988) dedicated exclusively to recording the unfortunately numerous quarry sections around the entire perimeter of the surviving portions of the site, four excavation areas and two trial trenches were dug (in total more than 220 m2) [Fig. 7].

Analysis of the data highlighted the importance of the lowest level, associated with a Neolithic cultural phase (about 1800-1100 BC) [Fig. 8] during which local hunter-gatherer communities acquired the technique of rice cultivation.

Fig. 2 Tha Kae: 1. Robbed tombs on the quarry margin in the “central island” at the start of the project (1988); 2. Mechanical excavators at work (1992) in the northern area of the site; 3. In the foreground, the entrance to tunnels dug by “grave robbers”, which in some cases extended as far as our excavation trenches, visible further back.

Fig. 8 Neolithic burials Age (c.1800-1100 BC). 1. Section B Tomb 3: a) necklace of Anadara shell beads; b) pottery drinking vessel with mineral temper and “incised and engraved” meander decorations. 2. Op.1 Tomb 10: a) freshwater clam (Fam. Unionidae) valve and Tridacna shell beads; b) plant-tempered vessels with thick red-brown slip and geometrical decoration painted in red.

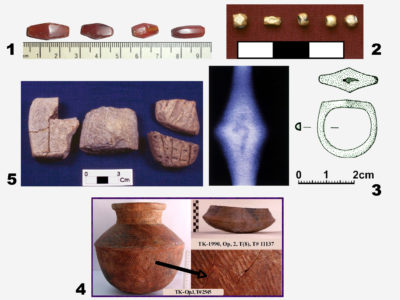

The use of rice husk as a tempering agent is well attested in the fabric of terracotta pots decorated with painted motifs [Fig. 9]. Both these vases and those with mineral tempers and sophisticated “incised and engraved” meander decorations were found as grave goods together with Anadarashell beads and “freshwater mussel” (Unionidae) valves [Fig. 10]. At Tha Kae the evidence relating to the introduction of copper metallurgy between 1100-1000 BC is weak. An important discovery dating to a mid-late phase of the local Bronze Age (c.800-500 BC) featured abundant processing waste and semi-finished artefacts derived from the production of jewellery from Tridacnashells and stone (quartzite and limestone). It was possible to reconstruct the entire manufacturing cycle [Fig. 10], and also to indicate relatively precisely – thanks to comparison with other Thai sites – the time when the products of this craft activity entered the inter-regional trading networks.

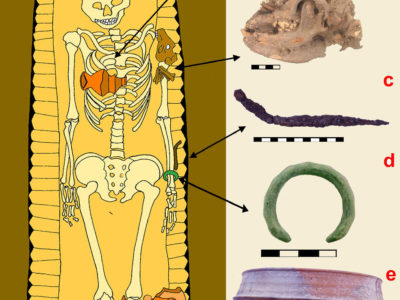

From the second half of the 1stmillennium BC long-distance trading, including the first recorded with the Indian subcontinent [Figs. 11, 12], the definitive adoption of the rice paddy, and the introduction of iron production triggered the growth of social complexity. At TK this is evident from the construction of the ditches and embankments around the village, and in the wealth differences displayed by the single and ‘family’ burials in the Iron Age burial ground [Figs. 13, 14]. This growth process culminated in the flowering of the Dvaravati artistic phenomenon in about AD 600-700. The remains of two brick structures are linked to this culture; due to their large size and the presence of small votive terracotta lamps, we assume they had a religious function [Fig. 15]. Various sophisticated Dvaravati artefacts (including cult objects), some found during our excavations and others given to the Thai FAD by private donors, testify to the importance of the moated site – by then within the orbit of the town of Lopburi/Lavo, which was probably due to the presence of a religious community (likely Hindu first and then Buddhist). This role did not diminish during the Khmer period (9th– 13th/14thcenturies), as evidenced by the presence in layer 1 of the deposit (about 10 cm thick) of numerous fragments of Khmer ritual glazed stoneware vessels and Chinese porcelain of similar date [Fig. 16]. The presence in several surviving patches within the uppermost layer of sherds of glazed stoneware from the Thai kilns in Sukhothai (13th-16thcenturies) and fragments of terracotta vases with imprinted decorations from the Ayutthaya period (14th– 18thcenturies) indicate the continuity of the settlement, which slowly moved towards the western edge of the river terrace during the last 300 years.